Project Assistant Professor, GSID, Nagoya University

Alla OLIFIRENKO

The first half of November brought a wave of new connections, ideas, and opportunities for learning. Nagoya University and our project were pleased to welcome visitors from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (Australia) and Ajou University (South Korea).

The convenience of modernity makes it easier than ever for researchers to collaborate across borders. Yet even in an age of real-time videoconferencing, nothing can stimulate the mind better than a human-to-human discussion. This made it only more precious to meet on campus with our Australian project member, Prof. Rajesh Sharma, who was accompanied by his colleague Prof. Reina Ichii from RMIT’s School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, as well as two engineering professors from the School of Science, Prof. Ravy Shukla and Prof. Selvakannan Periasamy, whose work focuses on technological innovation for efficient hydrogen generation. Later, we were joined by political scientists Prof. Pak Seoung Bin and Prof. Lee Youhyun from Ajou University, co-authors of a recent study with H2Governance members.

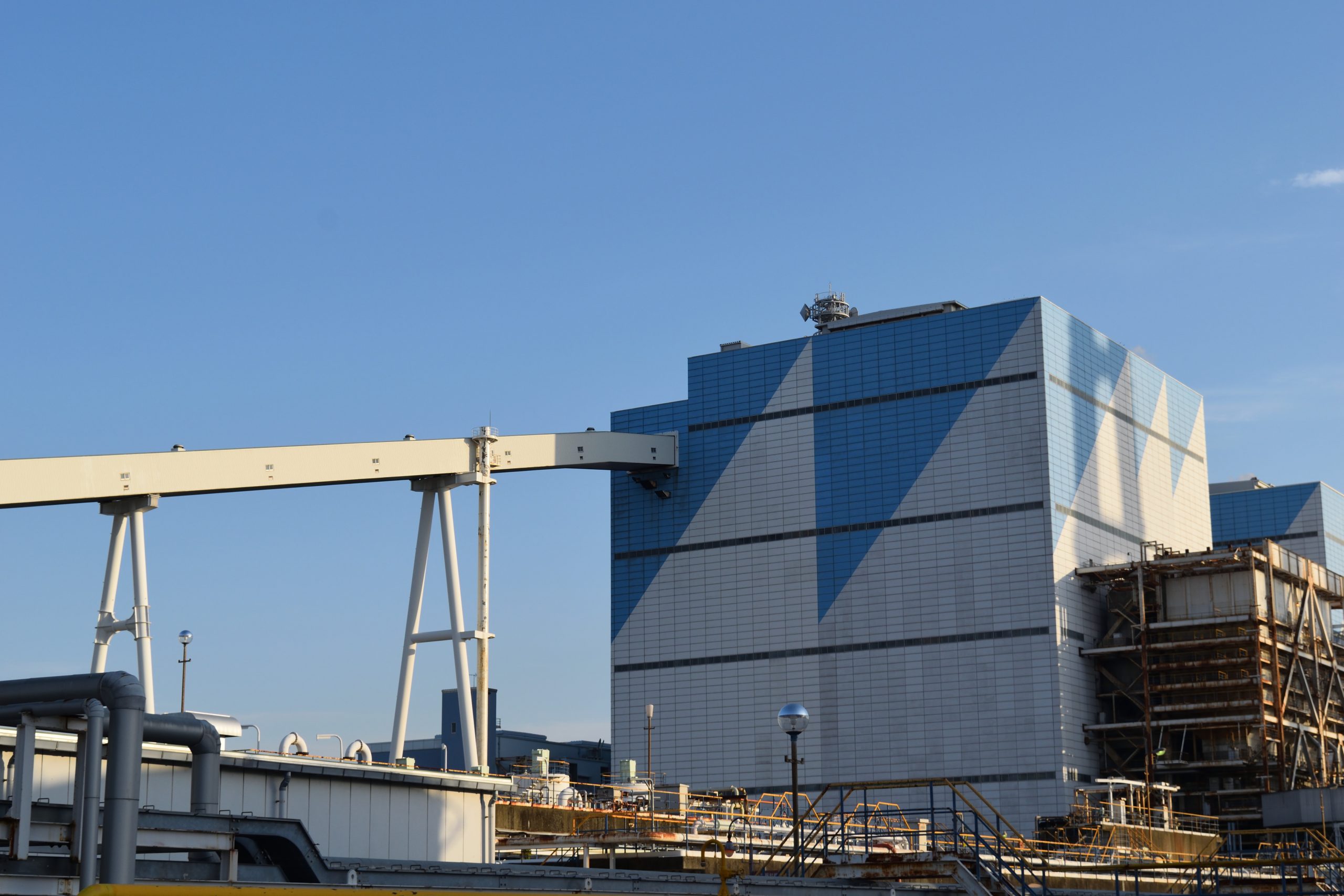

Visit to the Hekinan Thermal Power Station

On November 7, our group travelled to the Hekinan Thermal Power Station in Hekinan City, Aichi Prefecture, operated jointly by JERA Co., Inc. and IHI Corporation. The facility is not only a massive complex supplying roughly half of Aichi’s electricity, but also the site of the world’s first demonstration testing of large-volume fuel ammonia substitution at a large-scale commercial coal-fired thermal power plant.

In simple terms, part of the coal normally burned at the plant is replaced with ammonia, which produces no CO2 when combusted. This allows the plant to maintain the same level of electricity generation while lowering on-site carbon emissions.

But ammonia co-firing presents significant technical and environmental challenges.

First, substituting ammonia poses a risk of increasing emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulphur oxides (SOx). However, during the demonstration phase in April-June 2024, the Hekinan project successfully achieved 20% ammonia co-firing without increasing these toxic emissions.

Second, ammonia itself is a hazardous substance. Luckily, since it has long been used for exhaust gas treatment, the plant operator has long-term experience handling it safely.

Arguably, the most significant challenge for decarbonisation through ammonia is how to reduce the large carbon footprint associated with the production of ammonia, the majority of which is produced using fossil fuels. There are ways to produce clean ammonia – such as via electrolysis powered by renewables, or through biomass gasification, but the worldwide production capacities remain very low.

Global ammonia production is around 150 million metric tons annually – almost all of it using fossil fuels. Japan currently consumes slightly more than 1 million tons each year. Yet the Hekinan plant alone would require nearly half of Japan’s current consumption just to maintain a 20% co-firing rate. If Japan were to convert all thermal power generation to ammonia, it would need to import roughly 30 million tons per year, or about one-fifth of current total global production.

Ensuring a stable supply of clean ammonia is indeed an ambitious plan. However, it aligns with both Japanese national policy and JERA’s internal strategies. JERA aims for 20% ammonia co-firing by 2030 and 100% ammonia combustion by 2050, in line with its corporate net-zero target. According to METI’s Road Map for Fuel Ammonia, Japan expects to import 3 million tons of clean ammonia by 2030, with demand rising to 30 million tons by 2050.

The strategic idea here is not to replace coal and fossil fuels immediately, but rather to prepare for future developments and a gradual energy transition. By building infrastructure, refining combustion methods, and creating international supply chains now, Japan positions itself to adopt truly clean ammonia by the time production methods improve. Rather than waiting until clean ammonia becomes globally available, JERA has decided to make an upstream investment in low-carbon ammonia production in the US (the “Blue Point” project).

Workshop: “Social Science Challenges for the Dissemination and Expansion of Local Clean Energy Production Using New Technologies”

International discussion continued with our project, together with two related research projects – Kajima Foundation Research Grants for Specific Theme 'Empirical Study on the Social Acceptance of Low-Carbon Hydrogen Technology' and Social Science Challenges for the Dissemination and Expansion of Local Clean Energy Production Using New Technologies – hosting a workshop on Monday, November 10.

The workshop aimed to stimulate interdisciplinary discussion on the social, regulatory, and technological dimensions of hydrogen development, with a particular focus on Japan-Australia collaboration and the wider Asia-Pacific region. As the global energy transition accelerates, hydrogen deployment requires not only technical innovation but also clear regulatory standards, community trust, robust safety measures, and sustainable investment frameworks.

The workshop allowed the project members and guests to discuss the governance of hydrogen trade, technological innovation, and social acceptance through the lenses of law, policy, engineering, and social sciences.

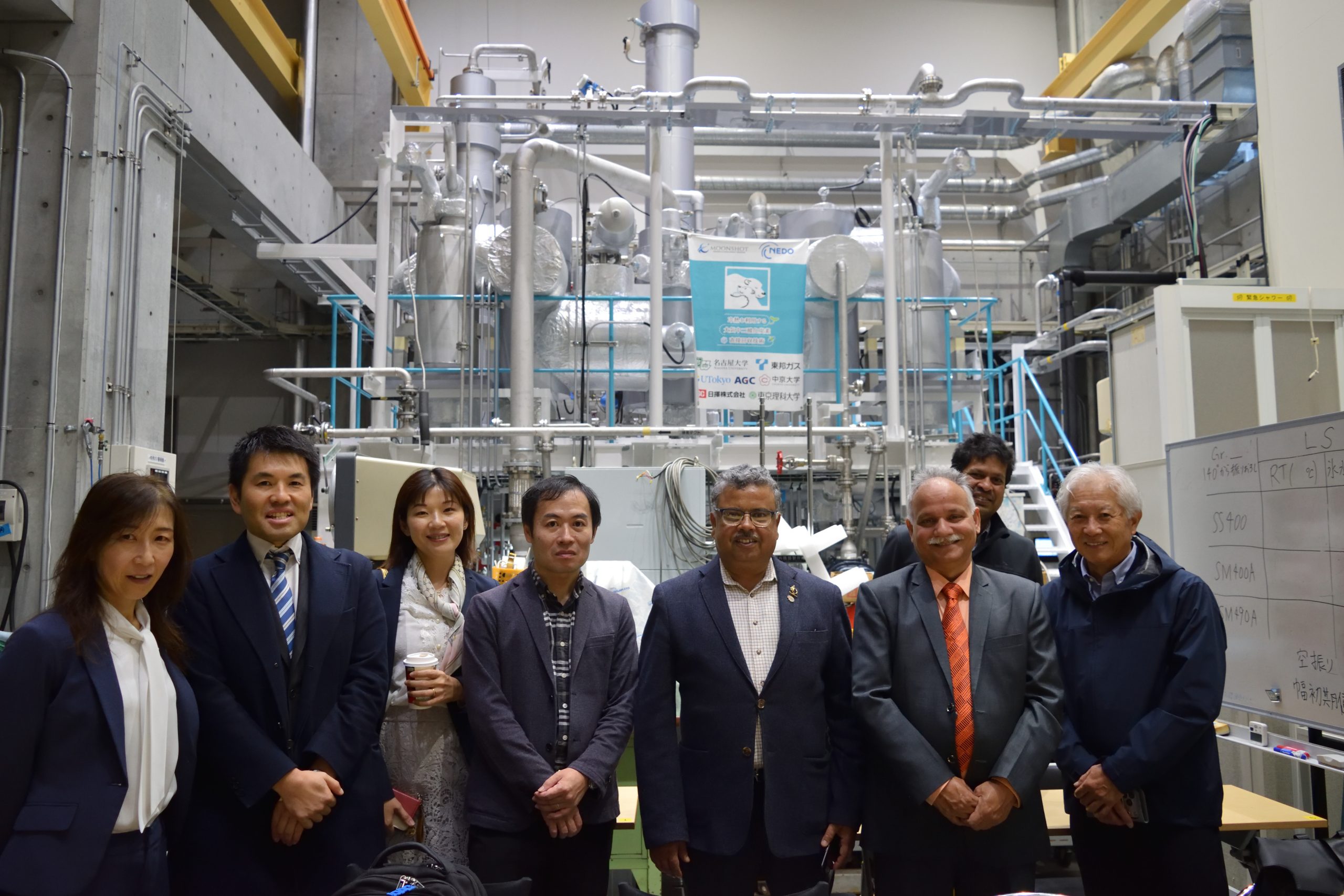

Later, the group visited the Cryo-DAC Benchscale Machine, co-developed by Nagoya University researchers including H2Governance project members Koyo Norinaga and Hiroshi Machida. Utilising excess cold energy released during the regasification of liquefied natural gas, this unique technology allows for direct air capture of carbon dioxide with significantly reduced energy consumption compared to conventional carbon capture methods. Although still at the experimental stage, the technology sparked a lively discussion among our engineering colleagues and inspired several future commercialisation ideas on the spot.

Together, the field visit and the workshop once again highlighted how interconnected are different facets of energy transition across countries and disciplines. Technology allowing for immediate reduction of CO2 emissions in Japan may leave a carbon footprint elsewhere. Conversely, countries that export coal to Japan may be contributing to offsetting carbon emissions by developing cleaner fuels that may eventually replace coal. Policy makers, economists, and business administration experts in Japan must account for this when building their strategies for decades ahead, especially when the technology progress remains uncertain.

The discussions we held in November provided a fresh angle on these complexities and reinforced our motivation to continue advancing H2Governance’s multidisciplinary research.